Initially, I saw movements mechanically. I focused on how each element worked and what influenced it to produce physical ‘movement’. However, while studying the chained movement of tightrope walking, I began to think about the expressive significance of physical movement.

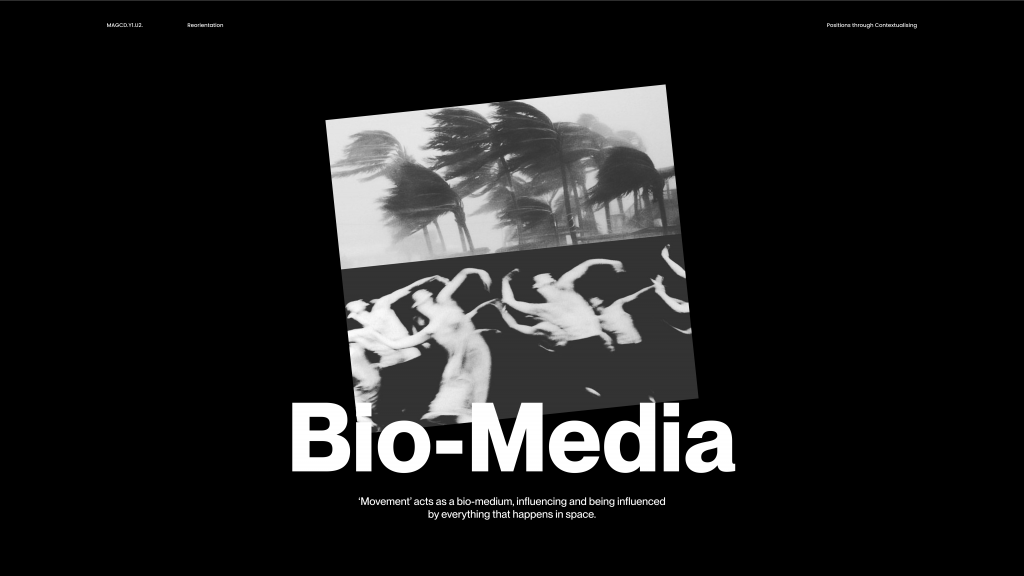

This led to the idea that ‘movement’ acts as a bio-medium, influencing and being influenced by everything that happens in space. I then decided to focus my research on ‘movement’ as a method or medium for transmitting and receiving content, rather than as a message in itself.

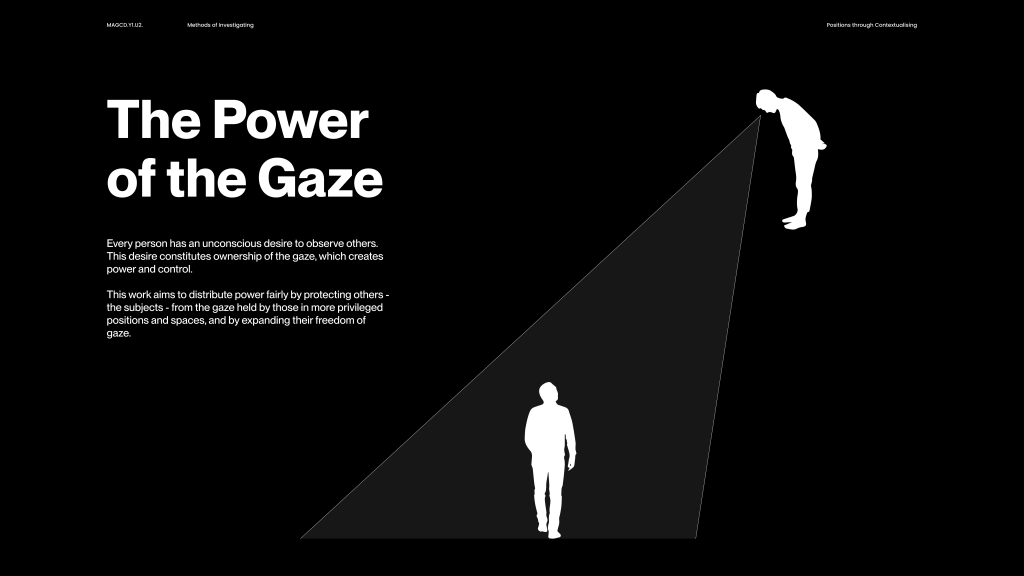

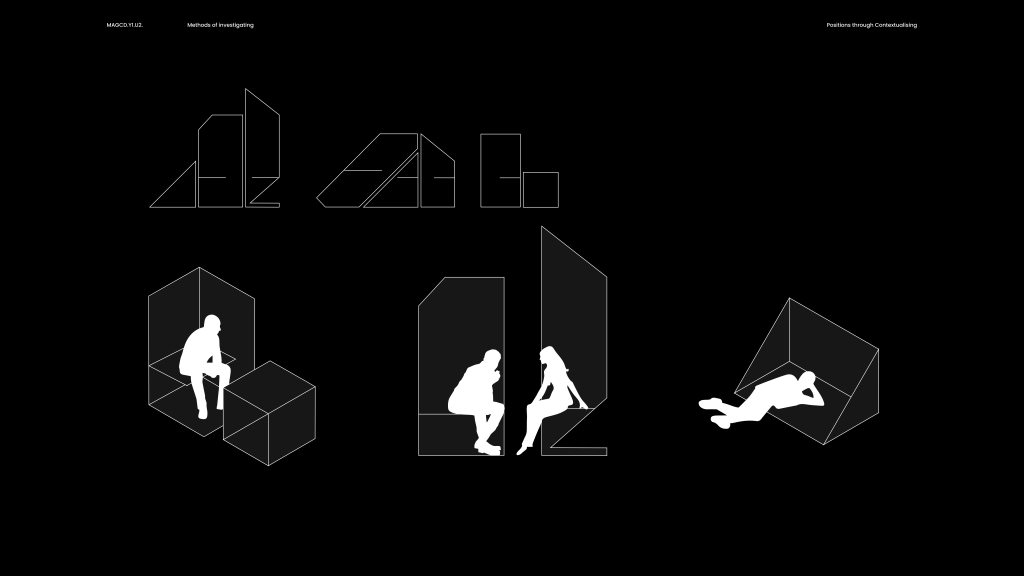

My biggest and oldest interest appeared in U1. Methods of investigating. It was the most unpolished and raw thoughts. In this project, I discovered and talked about power structures based on the position of individuals in public spaces such as student accommodation. By observing the students moving through the static structure of the space and what they were exposed to without being aware of it, I discovered the difference in gaze depending on the structure of the space they lived in.

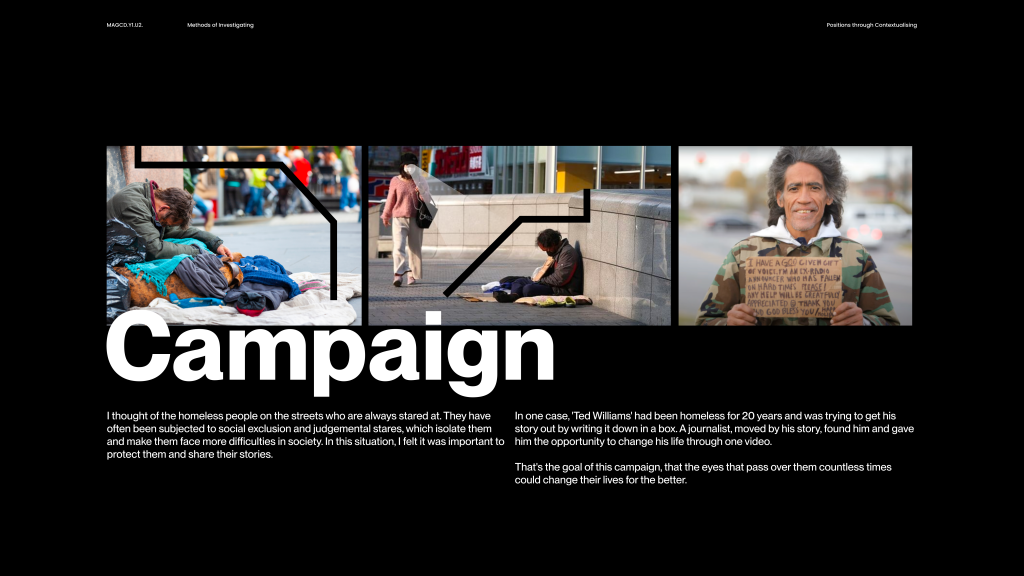

By designing furniture that can be freed from the gaze and a subsequent movement or campaign, I aimed to create lasting change by designing ‘The power of the gaze’ not as a project, but as a subsequent movement for people with similar experiences.

I was thinking about fixed spaces where people’s visibility is limited, and I thought of social media. Digital space is free and vast, but we spend most of our time in a very small, fixed space. All the while, all the data we see is being used by big companies to feed their algorithms. We are being controlled by invisible entities without even realising it.

Then, “How can we move away from the control of visibility that happens in static public spaces?”

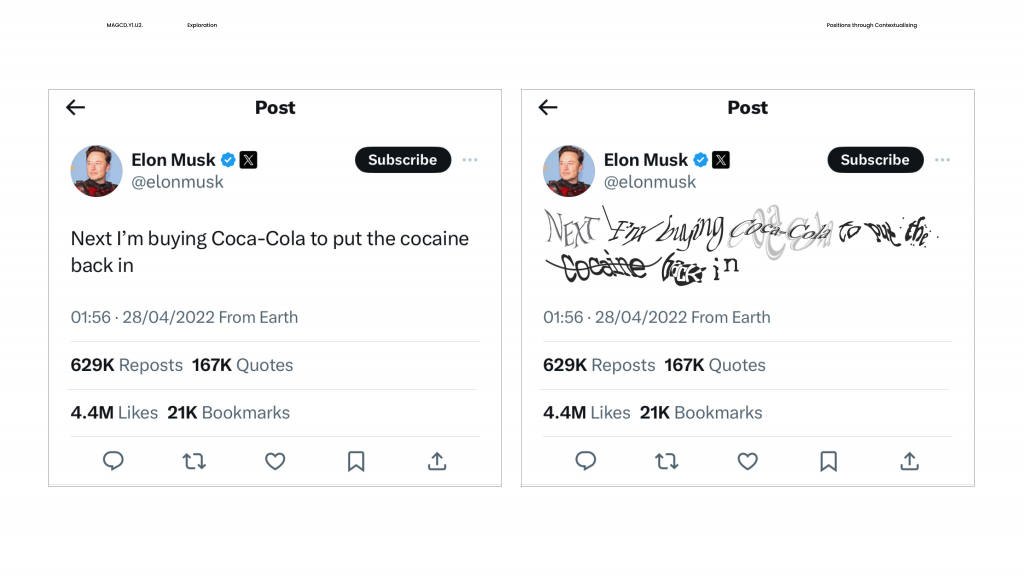

First, following this reference, we need to hack the control mechanisms. Computers are the medium of information collectors. I thought, what if we could make computers incapable of understanding what we see? A language that only humans (with a common set of rules) could discover.

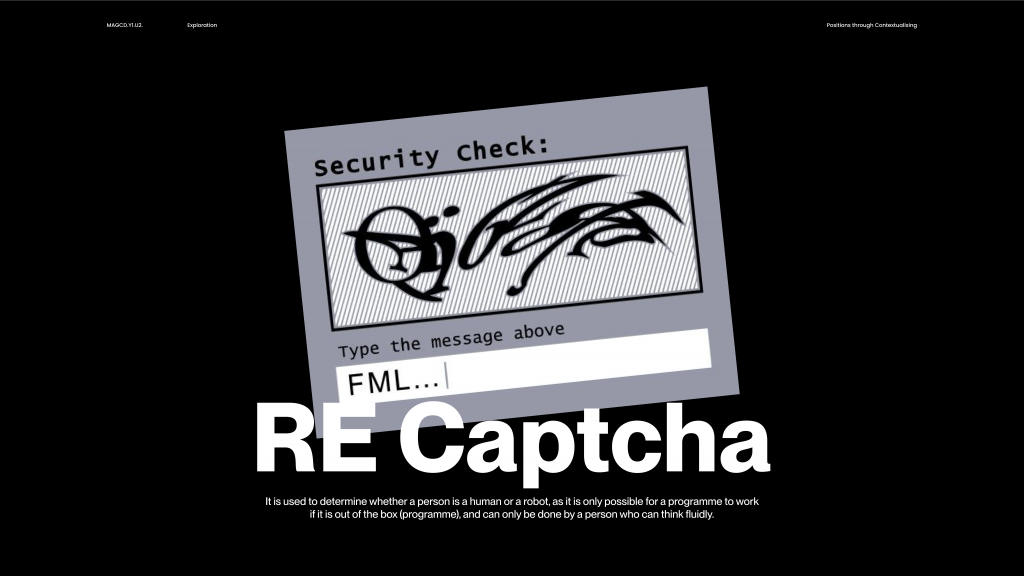

Then I remembered Re Captcha. It’s a series of puzzles designed to distinguish between a human and a robot.

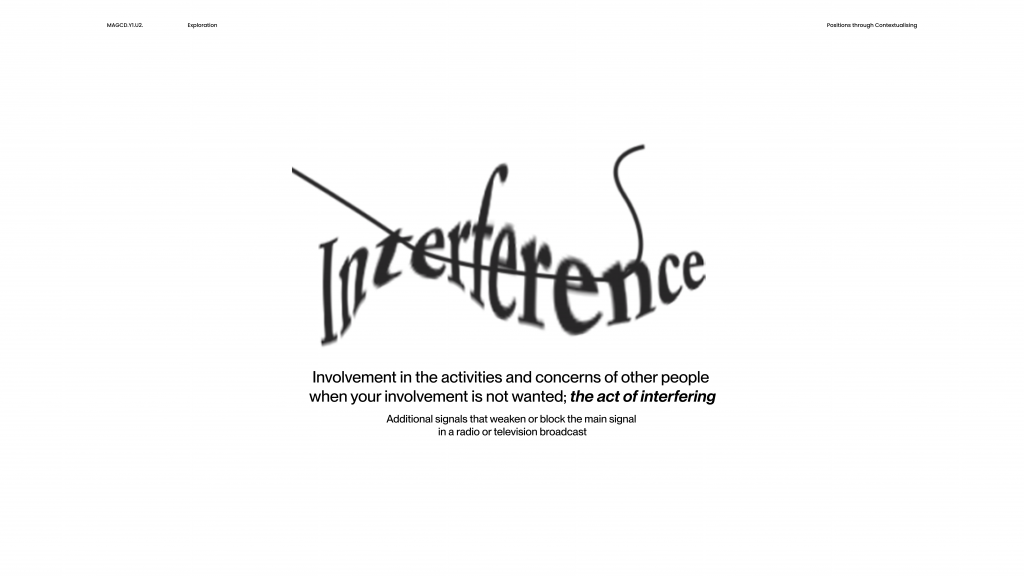

If the text on the screen is in the same code, the programme can guess it too, so it has a twist. The typography in ‘Re captcha’ is of poor quality, with dots and strikethroughs that obscure the text. We can read the text even with these distractions. This is because we perceive the text as a whole, rather than parsing it word by word, and we get information based on experience. Text is the easiest format for computers to understand, but we live in an age of images and video. Even on social media, we see more images than text. So how can images be distorted?

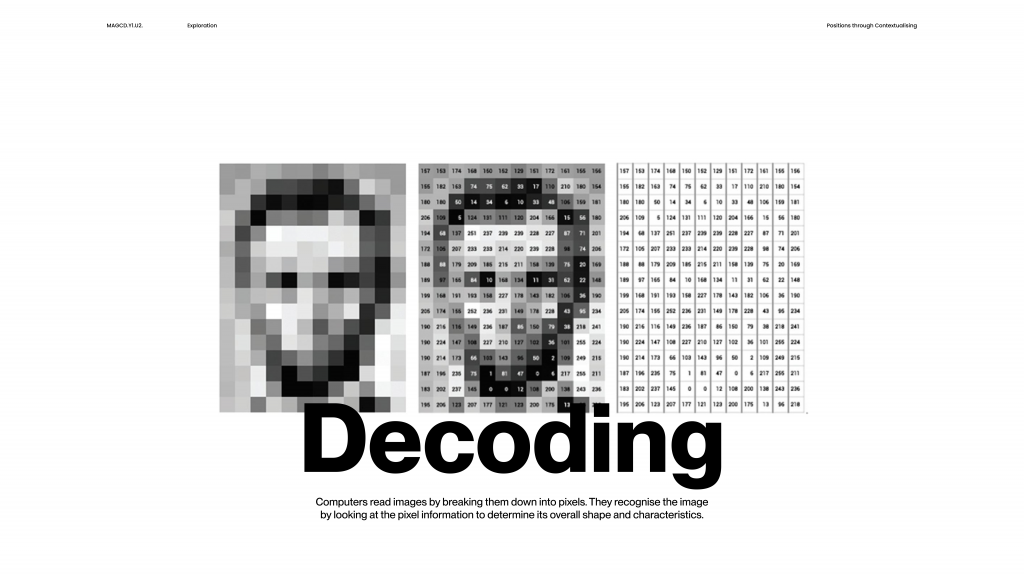

Computers read images by breaking them down into pixels. It finds information about the image by determining its overall shape and features. Is there a way to break up the pixels and make them read as a whole?

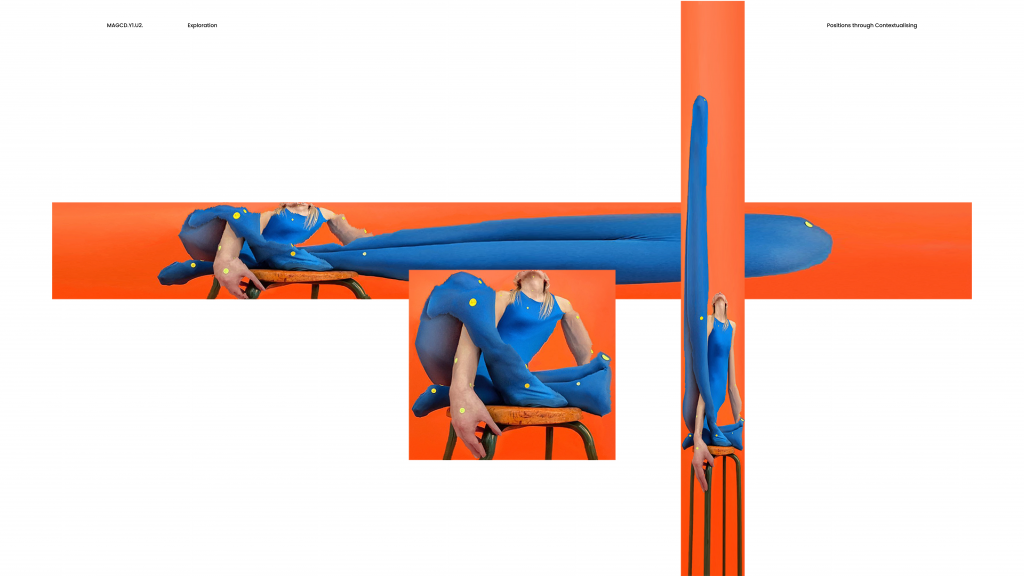

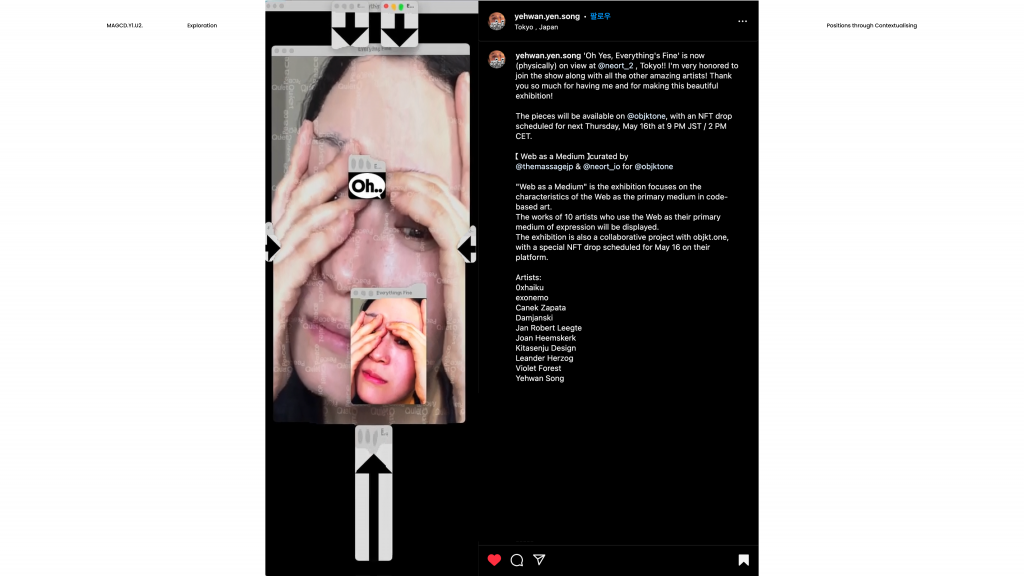

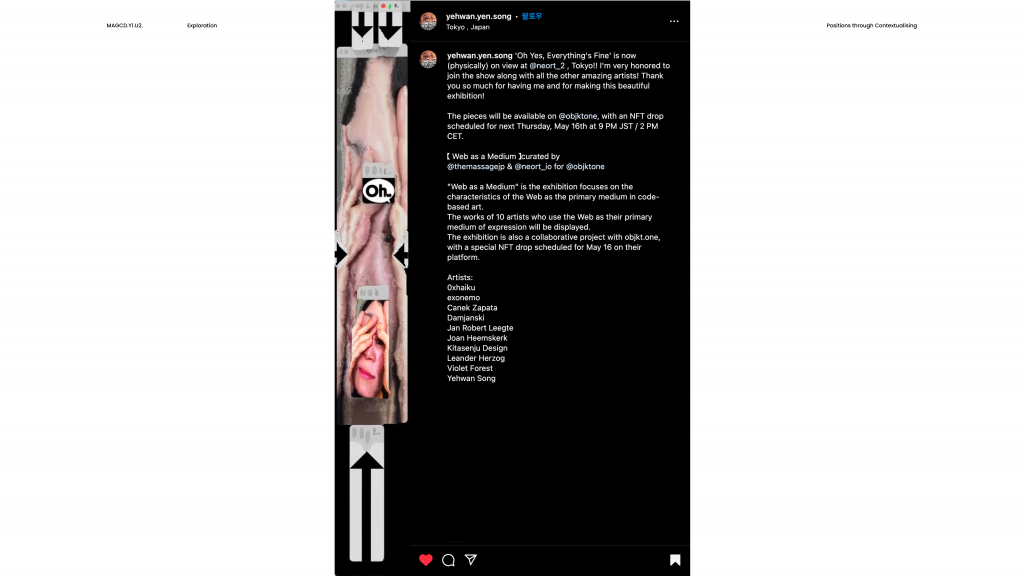

I experimented with the content-aware scale function in Photoshop. The image shrinks and expands, and the pixels are randomly broken up, but we can still read what the image is.

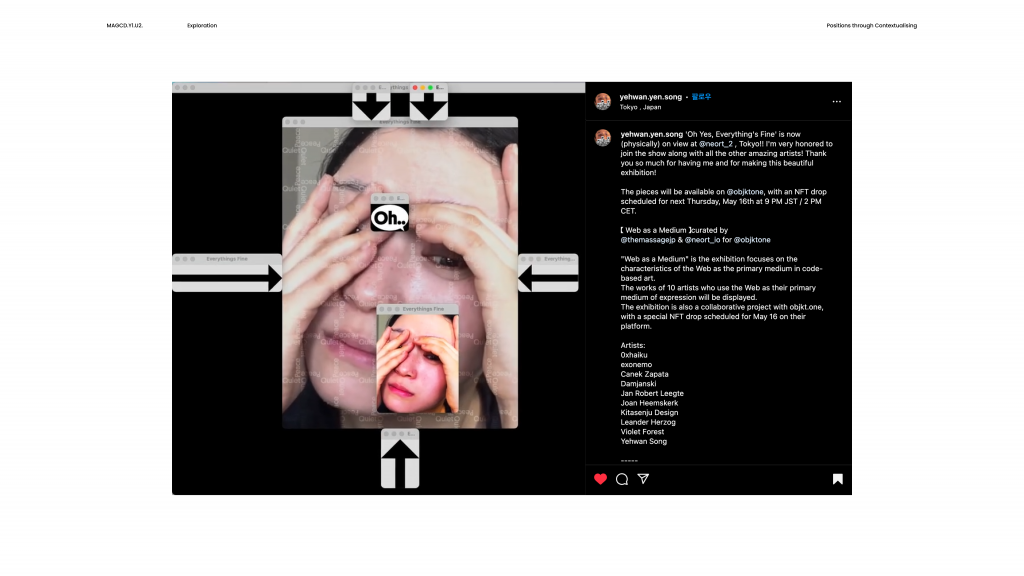

Now we know how to hack images and text. This is the last step, the media task. With the proliferation of digital devices, the user interface design system was established, and at the same time users became accustomed to a design system with uniform rules. Users should follow button positions, and all these gestures have become embedded in our subconscious. We use our thumbs to scroll text on small screens, and two fingers to zoom in and out of content.

Instead of gestures that are tailored to the fixed space of digital devices, I wanted to work with movements that we can talk about with each other. I adopted the basic ‘hiding’ gesture as a way of escaping the gaze of computers, AI and invisible things in control.